Housing Loans and rapidly increased interest rates have been killing the ultimate dream. What once was referred to as the most safest investment is now unavailable to the most. Back in the day, people had the ability to buy their home without loans and collateral but now; the only way people buy houses are through loans and spend their entire lives repaying the loan.

The shock that rippled through global housing markets as central banks rapidly raised interest rates last year has given way to a cold new reality: the real estate bonanza that fuelled wealth for millions of people is over.

Markets around the world are caught between sharply higher borrowing costs – likely here to stay – and a shortage of homes that’s keeping prices elevated. That’s made housing in many areas even less affordable, while property owners with resetting loans face increasing financial strain.

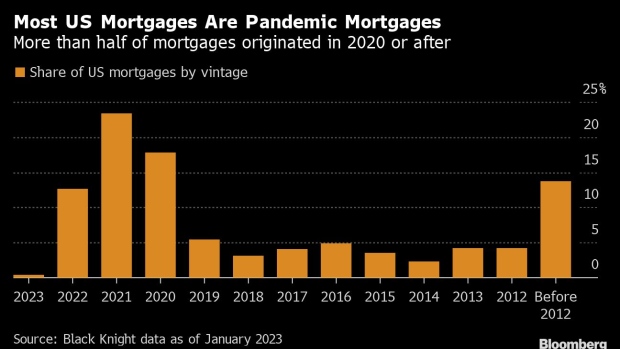

The USA market, dominated by 30-year mortgages, is effectively frozen as home owners with low rates are reluctant to sell, and buyers are squeezed.

In the long-time boom areas of New Zealand and Canada, values haven’t fallen meaningfully for house hunters, and people who paid peak prices are now struggling with higher loan payments. From the UK to South Korea, distress is mounting for landlords. And in many places, higher interest rates are only making it harder to build.

The scenarios may be playing out differently in each country, but they all add up to a potential drag on global economies as people shell out more of their income for housing, whether they rent or own.

And with buyers increasingly locked out, the viability of home ownership as a path to middle-class security – a bedrock of personal finance for generations around the world – is suddenly looking a lot more difficult.

The winners are long-time owners who have captured equity from soaring values or don’t have a mortgage, freeing them to put cash in higher-yielding investments.

Zandi expects that US 30-year mortgage rates, currently about 7.4%, will average somewhere around 5.5% over the next decade, compared with a low of 2.65% cent in early 2021. Most other developed countries will see a similar increase, he says, even if particular levels vary.

A lot remains unknown. A deepening war in the Middle East and the ongoing economic troubles of China – contending with its own series of property crises centred on its highly indebted developers – could contribute to a broader global downturn that would reduce housing demand and push down prices substantially, causing far worse financial turmoil. And in terms of real estate, commercial property has become more worrisome for the economy.

But even as inflation cools and many countries’ rate rising campaigns are easing, consumers are starting to come around to the idea that borrowing costs may never be as low as they were in the 15 years since the financial crisis.

The problem with Housing Loans is being referred as to ‘Glacial Period’ in the States

In the US, the collision of low inventory, rising prices and the highest mortgage rates in a generation has sent sales of previously owned homes to the lowest level since 2010, according to the National Association of Realtors.

The market is now the least affordable in four decades, with about 40% of the median household income required to purchase a typical home, data from Intercontinental Exchange show.

In a report last month, Goldman Sachs economists said the impact of sustained higher mortgage rates would be the most pronounced in 2024. They estimated that transactions would fall to the lowest level since the early 1990s.

“In some ways we’re in the early stages of this glacial period, and it’s unlikely to thaw any time soon,” says Benjamin Keys, a professor at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “This weirdness can last for a long time.”

That stands to have knock-on effects. Mobility for jobs could be limited, family members and friends may more often be forced to live together and, as the elderly age in place, homes may be kept off the market that could otherwise be purchased by younger families.

“Things might get a little more affordable, but certainly not to what people would have hoped for,” says Niraj Shah, an economist with Bloomberg Economics. “It’s going to be a struggle on both ends.”

He predicts a “slow puncture” in prices for developed economies rather than a crash, saying that an economic slowdown is unlikely to result in heavy job losses that would cause severe housing distress. “You have distressed people, but not distressed sales,” he says.

The most extreme scenario of Housing Loans is unfolding in New Zealand; they are watching their pennies

One of the most extreme cases is playing out in New Zealand, which was home to one of the world’s biggest pandemic booms, with property prices rising almost 30% in 2021 alone.

About 25% of the current stock of mortgage lending was taken out that year, and a fifth of those were first-time buyers, according to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

Mortgage rates in the country are typically fixed for less than three years – meaning the central bank’s 525 basis points of rate increases since October 2021 are sending house payments soaring.

That’s squeezing the budgets of people such as Aaron Rubin, who took out a $NZ1 million ($920,000) mortgage in 2021 to finance the purchase of a $NZ1.2 million four-bedroom house.

After moving to New Zealand from the US eight years ago, he and his wife, Jessica, thought buying a home in the coastal city of Nelson was a decision that would provide stability for their two young children. At first, the couple paid about $NZ4000 a month on their mortgage. After a refinancing, it’s now up to about $NZ6400.

“We can no longer afford to visit our family in the US, and we are literally watching every penny that flows in and out of the account,” says Aaron, a 46-year-old software engineer. “It’s time-consuming and stressful, and it’s changed our lifestyle.”

He considers himself lucky – his financial situation isn’t dire, and the couple can afford to continue paying their mortgage. He sees many Kiwis under far greater pressure.

“Once you deflate it by household income growth, debt is actually considerably lower than it was in 2007,” she says. “But, of course, the average hides a million stories, and there are certainly some stressed people out there.”

Increasing Housing Loans and Increased Interest Rates is seeing the investors walkout

The global housing boom of the last decade made real estate a fast path to wealth in countries such as New Zealand, Australia and, especially, Canada, where tens of thousands of people turned into amateur investors.

“I don’t see how you can replicate the last 20 years going forward,” says Robert Kavcic, the Bank of Montreal economist who authored the report. “You’re going to have a whole generation of investors learn a pretty hard lesson.”

Higher borrowing costs have already pushed some investment properties deep into negative cash flow, forcing their owners to sell while also damping interest in new purchases. That could spell trouble for regular people just looking for a place to live, too.

Investors buying units pre-construction has become a key source of financing for developers in the last decade, and their pullback has already seen the delay or cancellation of thousands of planned units in cities such as Toronto.

Canada’s already under-supplied market is one reason home prices have proved surprisingly resilient to higher interest rates, and the expected slowdown in building could only exacerbate the shortage.

A similar situation is playing out in Europe, where higher rates and soaring construction costs threaten to intensify supply strains. In Germany, new building permits fell more than 27 per cent in the first half of the year, and in France they dropped 28 per cent through July.

Sweden, suffering its worst slump since a crisis in the 1990s, has building rates running at less than a third what’s deemed necessary to keep up with demand, threatening to further test the limits of affordability.

And that’s not even getting into the compounding strain from skyrocketing consumer prices generally. In the UK, which is facing the highest cost-of-living increase in a generation, nearly two million people have resorted to using buy now, pay later credit to cover groceries, bills and other essentials, according to a survey this year by the Money and Pensions Service.

A report released in September by KPMG showed almost a quarter of UK mortgage holders were considering selling and moving to a cheaper property due to the surge in financing costs, and mortgages with late payments now account for more than 1 per cent of the value of outstanding home loans.

London landlord Karen Gregory had little choice but to sell her building after her mortgage payment jumped more than threefold, leaving her with the prospect of evicting a young couple with a baby on the way. They found a new home before her deal, but the situation left her fed up. “Landlords have had enough of the increase in interest rates,” she says.

Housing Loans issue has Asia under its wraps

In Asia, South Korea is contending with its own landlord fallout. The country has the developed world’s highest ratio of household debt-to-gross domestic product, at 157%, if the roughly $US800 billion ($1.2 trillion) is counted from “jeonse” – a rental system unique to the country.

Under the system, landlords collect a deposit called jeonse that’s equal to roughly half of a property’s value at the start of the lease period, which typically runs for two to four years. When interest rates go up, jeonse becomes less attractive than paying monthly rent and the size of the deposits landlords can get from renters falls.

Hong Kong, meanwhile, has been hit by China’s slowdown, a population exodus and rising rates that have halted once-unstoppable price gains.

Since its currency is pegged to the greenback, the city’s monetary policy generally moves in tandem with the US. That’s caused mortgage rates to more than double since the beginning of 2022.

Existing home prices in the notoriously expensive areas have fallen to a six-year low, builders are offering deep discounts, and the government is slashing extra stamp duties for some buyers to revive the hub. Unless interest rates start falling, the Hong Kong housing market will continue to suffer.